- Home

- Adélia Prado

The Mystical Rose

The Mystical Rose Read online

ADÉLIA PRADO

THE MYSTICAL ROSE

Selected Poems

Adélia Prado was “discovered” when she was nearly 40 by Brazil’s foremost modern poet, Carlos Drummond de Andrade, who was astonished to read her ‘phenomenal’ poems, launching her literary career with his announcement that St Francis was dictating verses to a housewife in the provincial backwater of Minas Gerais. Psychiatrists in droves made the pilgrimage to Divinópolis to delve into the psyche of this devout Catholic who wrote startlingly pungent poems of and from the body; they were politely served coffee and sent back to the city. After publishing her first collection, Baggage, in 1976, she went on to become one of Brazil’s best-loved poets, awarded the Griffin Lifetime Achievement Award in 2014.

Adélia Prado’s poetry combines passion and intelligence, wit and instinct. Her poems are about human concerns, especially those of women, about living in one’s body and out of it, about the physical but also the spiritual and the imaginative life; about living in two worlds simultaneously: the spiritual and the material. She also writes about ordinary matters, insisting that the human experience is both mystical and carnal. For her these are not contradictory: ‘It’s the soul that’s erotic,’ she writes.

‘Sometimes other poets and critics analyse my writing, and they’ve said how, even though the text is made of colloquial and everyday language, the work goes to transcendental issues. I don’t know, I don’t explain things; I simply do what I do. I only know how to write about concrete, immediate and commonplace things. But these commonplace things show me their metaphysical nature. I can only see the metaphysical, the divine, through the concrete and the human.’

‘Brazil has produced what might seem impossible: a really sexy, mystical, Catholic poet’ – Robert Hass.

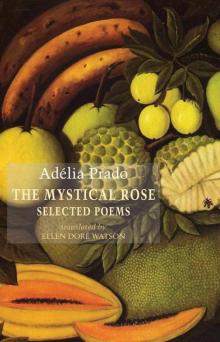

COVER PAINTING (DETAIL)

Still Life with Exotic Fruits (1908) by Henri Rousseau

Adélia Prado

THE MYSTICAL ROSE

Selected Poems

translated by

ELLEN DORÉ WATSON

CONTENTS

Title Page

Introduction by ELLEN DORÉ WATSON

Acknowledgements

from BAGGAGE (1976)

Dysrhythmia

Successive Deaths

Vigil

With Poetic Licence

Before Names

Lesson

Guide

Head

Two Ways

Praise for a Colour

Purple

Seductive Sadness Winks at Me

Window

Heart’s Desire

The Girl with the Sensitive Nose

Seduction

At Customs

Easter

Love Song

Serenade

from THE HEADLONG HEART (1978)

Concerted Effort

Not One Line in December

Day

A Man Inhabited a House

Lineage

A Good Cause

A Fast One

Absence of Poetry

Blossoms

Young Girl in Bed

The Black Umbrella

Passion

Neighbourhood

Murmur

Dénouement

from LAND OF THE HOLY CROSS (1981)

The Alphabet in the Park

Trottoir

Pieces for a Stained-Glass Window

Land of the Holy Cross

Falsetto

Some Other Names for Poetry

Tyrants

Love in the Ether

Consecration

Legend with the Word Map

Professional Mourner

Mobiles

from THE PELICAN (1987)

Fibrillations

Lily-like

The Mystical Rose

The Sphinx

The Transfer of the Body

God Does Not Reject the Work of His Hands

Object of Affection

Responsory

Eternal Life

Sleeping Beauty

Heraldry

The Birth of the Poem

Two O’Clock in the Afternoon in Brazil

The Dark of Night

Nigredo

The Good Shepherd

Divine Wrath

The Holy Face

The Battle

Ardent Memory

The Third Way

Sketchbook

Syllabication

Crazy Behaviour

Furious with Jonathan

The Sacrifice

The Pelican

Silly Girl

from KNIFE IN THE CHEST (1988)

Biography of the Poet

The Meticulous One

Laetitia Cordis

History

Immolation

Opus Dei

In Portuguese

Parameter

Words and Names

The Tenacious Devil Who Doesn’t Exist

Matter

Form

Lighter Than Air

Guess

One More Time

Letter

Note from the Daring Damsel

One Thing After Another

Marvels

Trinity

The Last Supper

Pastorals

The Hermit’s Apprentice

from ORACLES OF MAY (1999)

The Poet Wearies

God’s Assistant

Salve Regina

Buried Treasure

Staccato

Domus

A Good Death

Poem for a Girl Apprentice

On Love

Portunhol

Nap with Flowers

Mediation Verging on a Poem

Mural

Our Lady of Conception

Mater Dolorosa

Chamberpot

Invitational

Christ’s Passion

Application for Adoption

Woman at Nightfall

Meditation of the King Among His Troops

Rebuke of Pride

October

Human Rights

Just Like a Man

Ex-Voto

Anamnesis

Holy Icon

Saint Christopher Transit

Spiritual Exercise

The State of May

Neopelican

About the Author

Copyright

INTRODUCTION

‘Compared to my heart’s desire / the sea is a drop.’

Adélia Prado’s poetry is one of abundance. These poems overflow with the humble, grand, various stuff of daily life – necklaces, bicycles, fish; saints and prostitutes and presidents; innumerable chickens and musical instruments. And, seemingly at every turn, there is food.

I first met Adélia Prado in 1985, in her kitchen in her home town of Divinópolis. Ever since stumbling on a badly-translated seven-line poem of hers, I had been wanting to sit across a table from this woman and talk about translating the rage and delight of her poetry into English. Years later, when I arrived on her doorstep, manuscript of translations in hand, and blurted out that I was famished, she was visibly pleased – the only previous North American she had met had refused to eat a thing – and sat me down to a huge meal of beans and rice with all the trimmings.

Appetite is crucial to Prado:

Forty years old: I don’t want a knife

or even cheese –

I want hunger.

The poet cooks, eats, chews memories, confesses to gluttony: ‘I nibble vegetables as if they were carnal encounters.’

Sexual hunger is admitted as frankly as any other. We see a woman tempted by ‘the vibrations of the flesh’, by ‘t

he precise configuration of lips’, who listens ‘most closely to the voice that is impassioned’, a ‘woman startled by sex / but delighted’.

There is an abundance of dark things also: ‘drowning victims, chopping blocks, / forged signatures’. There is cancer. There are moments of quiet desperation:

What thick rope, what a full pail,

what a fat sheaf of bad things.

What an incoherent life is mine,

what dirty sand.

The appeal of these poems has to do with their wonderful specificity, their nakedness, and their desire to embrace everything in sight – as well as things invisible. Here is a ‘creature of the body’ who experiences great spiritual craving, and believes that the spirit is almost as palpable.

After all, the divine is only accessible to us via the concrete stuff of human existence. ‘From inside geometry / God looks at me and I am terrified.’ The very thought inspires fear and awe, but it is an intimate, face-to-face spiritual encounter Prado is after: the word made flesh. She craves

something that neither dies nor withers,

is neither tall nor distant,

nor avoids meeting my hard, ravenous look.

Unmoving beauty:

the face of God, which will kill my hunger.

What is truly astonishing in all this abundance of appetites is that Prado seems to revel in turning them loose in the same poem. What some people might see as contradictory impulses appear and reappear obsessively, overlap and intertwine. For Prado, this is not only a fact of life but also the first step to understanding what it’s like to live both in our bodies and out of them. ‘It’s the soul that’s erotic,’ she declares in one poem, and in another: ‘I know, now, that my erotic fantasies / were fantasies of heaven.’ Hunger for living inspires hunger for the life beyond the grave: ‘There’s no way not to think about death, among so much deliciousness, and want to be eternal.’ If God possesses an ‘unspeakable seductive power’, it is also true that ‘a voluptuous woman in her bed / can praise God, / even if she is nothing but voluptuous and happy.’

On the other hand, if at times ‘Sex is frail, / even the sex of men’, so is belief, whose buoyancy does not cancel the unacceptability of mortality. Death is a ‘trick’. At times Prado is ‘tempted to believe that some things, / in fact, have no Easter.’ The ‘furious love’ of God, ‘Who is a big mother hen’, is often hard to understand.

He tucks us under His wing and warms us.

But first He leaves us helpless in the rain,

so we’ll learn to trust in Him

and not in ourselves.

One of Prado’s greatest gifts is the knowledge that embracing life means embracing impossible contradictions. The fear of death is inseparable from the pleasure of simply living. In ‘The Birth of the Poem,’ she explains why she writes: ‘it’s the spirit driving me, / wanting to be adored’ but then in ‘The Poet Wearies, she rebels: ‘I’ve had it with being Your herald.’ Sometimes one poem, or one line, seems to take back what another has said – ‘what I say, I unsay’. But she also says: ‘what I feel, I write’. For Prado, writing is a way to stay whole and sane: ‘Poetry will save me.’ A way to gather together, kicking and screaming, all the diverse reactions she has to the wide worlds – this one and the next.

This is a poetry of joy and desperation. Disarmingly childlike questions (‘Does Japan really exist?’), the curious wonder of maps, mirrors, and trellises live alongside suicides, goose bumps, and shards of glass. I was not the least bit surprised that Prado’s toast, over the shot of cachaça that followed the beans and rice, was ‘All or nothing!’

Saint Francis in the State of General Mines

Adélia Luzia Prado de Freitas was born and has spent all her life in the provincial, industrial city of Divinópolis, in Minas Gerais, a landlocked state of baroque churches, rugged mountains, and mines (hence the name). Minas is also known for producing more writers and presidents than any other state in Brazil, though Prado says of herself: ‘I am a simple person, a common housewife, a practising Catholic.’ Since Mineiros are famous for their cautious self-containment, her words cannot be taken at face value. Behind modesty and simplicity is the courage of a woman contesting taboos and traditions, a woman who extracts from her daily life in a small town of the interior extraordinary poems in which the sensual and the mystical, the sacred and the profane, fuse with unusal vividness.

Prado comes from a family of labourers, full of big life and small expectations, whose men worked for the railroad or ran small groceries and whose women (her mother and grandmothers) died in childbirth. From the start, she was the dreamer of the family, often accused of being lazy and odd because she liked nothing better than to stare off into space. ‘Of my entire family, I’m the only one who has seen the ocean,’ she says in ‘Dénouement’, and, in ‘Lineage’, ‘None of them ever thought of writing a book.’ The first in her extended family to go to college, she earned degrees in philosophy and religious education, and taught the latter in public schools until 1979. Married, with five grown children and eight grandchildren, she worked for a time as cultural liaison for the city of Divinópolis, but now dedicates her time to family and writing.

Prado’s literary career began relatively late – and with a bang – when elder statesman of Brazilian poetry Carlos Drummond de Andrade announced in his Rio de Janeiro newspaper column that Saint Francis was dictating verses to a woman in Minas Gerais. Though she had started writing when very young, she showed no one her work, and began to consider it poetry only in her late thirties, when she completed the manuscript of her first collection, Bagagem (Baggage). Drummond’s pronouncement brought publishers to her door, and in the years since she has produced eight individual books of poetry, seven of poetic prose, and one children’s book, steadily gaining recognition and admiration. The theatrical production of her work, Dona Doida: Interlude (somewhat like the one-woman show of Emily Dickinson’s work, The Belle of Amherst), performed by the great Brazilian actress Fernanda Montenegro, was a sensation in 1987, playing to packed houses in Rio for nine months before a national tour the following year. In 1998, when the Brazilian National Library’s Jornal de Poesia polled intellectuals to compile the ‘List of Twenty’ foremost living poets, she was ranked fourth. Recipient of many accolades in her native country, Prado now has multiple books in Spanish and English, and translators working actively in Polish and Chinese. This past June, the Griffin Trust for Excellence in Poetry honoured her with their Lifetime Achievement Award, previous recipients of which include Seamus Heaney, Tomas Tranströmer, Yves Bonnefoy, and Adrienne Rich.

Prado prefers to keep out of the limelight for the most part, travelling infrequently to Rio or São Paulo for interviews or literary festivals. Though she has been a member of Brazilian writers’ delegations to Portugal and to Cuba, she has little interest in cultivating literary contacts and takes no part in academic life. Her friendships with other writers are more about friendship than writing.

Traditional poetic forms and metrics find their way into Prado’s poetry in spirit only, transformed into free verse based on the music of the human voice, the melody and rhythm of the colloquial Portuguese spoken in Minas Gerais. Biblican strains, particularly from Psalms and the Song of Solomon can frequently be heard, as well as the poetry of the Mass and other Catholic rituals. The interplay of these various levels of diction reflects and underlines the constant give-and-take between human and divine in the sensibility that fuels the poems.

Certainly Prado’s work has been influenced by the great poets of Brazilian modernism – Manuel Bandeira, Oswald de Andrade, Jorge de Lima, Carlos Drummond de Andrade, among others – especially in ironic humour and linguistic inventiveness. Several poems (not included here) acknowledge and explore her complex literary relationship with Drummond, the fellow Mineiro whose enthusiastic response brought her work to the attention of the rest of Brazil. When Prado is asked to name writers who have mattered to her, the first is invariably Guimarães Rosa

(another Mineiro), said by some to be Latin America’s greatest novelist, whose spiritual and linguistic presence is strong in these poems. Prado is a voracious reader of works in translation, as well, from Saul Bellow to Carson McCullers to Ernest Becker to Carl Jung.

Her work depends very little on literary predecessors, however, springing almost entirely from her experience of daily and spiritual things, and the resulting authenticity has stunned many critics. ‘I find these poems brutal, marvellous, and astonishing,’ writes Margarida Salomão, in the preface to Bagagem. ‘This is a work before which critical discourse shrinks back, ashamed of all the abstractions, labels and schematics at hand, leaving to the reader’s fascination this territory in which exuberance and clarity are not yet separated.’ In a review of that first volume, poet and critic Affonso Romano Sant-Anna suggests that ‘Adélia Prado’s success is due to the irrational and provocative power of her poetry…. Her poems leap past the cerebral and insufferable poetry of the last twenty years.’

That the leaps these poems take seem convincingly uncalculated does not mean we are in the presence of a naïf. As poet Ferreira Gullar insists, ‘Prado’s poetry is simple but not simple…. The overall impression is of a spontaneity that hides complexity and mastery.’ Hers is an elusive mastery, more a gift than an act of will, which she has developed in private, and which is virtually impossible to imitate successfully. ‘Some writers invent a rhetorical sleight-of-hand, patent it, and think it constitutes style,’ continues Romano Sant-Anna. ‘I’m talking about something else: a way of knocking the feet out from under us, leaving us humble and foolish in the face of a truth revealed.’

Drummond’s pronouncement rings true: ‘Adélia is lyrical, biblical, existential; she makes poetry as naturally as nature makes weather.’

Emotional Weather

One of the things I like most about Prado’s work is that her poems resist explication as thoroughly as they resist labels. They are neither obviously experimental nor easily traceable to a particular poetic forebear. They are fervent without agreeing to be partisan. They make conflicting claims, they admit to being pulled in opposite directions, they change their many minds.

The Mystical Rose

The Mystical Rose